Vocabulary Flashcards

Fear

Click to see definition

A strong feeling of being scared or worried about danger

Control

Click to see definition

To have power over something or someone

Punish

Click to see definition

To hurt or make someone suffer because they did something bad

Ancient

Click to see definition

Very old; from a long time ago

Strict

Click to see definition

Demanding that rules are obeyed; not allowing freedom

Empire

Click to see definition

A group of countries ruled by one leader or government

Crime

Click to see definition

An action that breaks the law

Trade

Click to see definition

Buying and selling things between people or countries

Society

Click to see definition

All the people living together in a country or area

Government

Click to see definition

The group of people who control a country

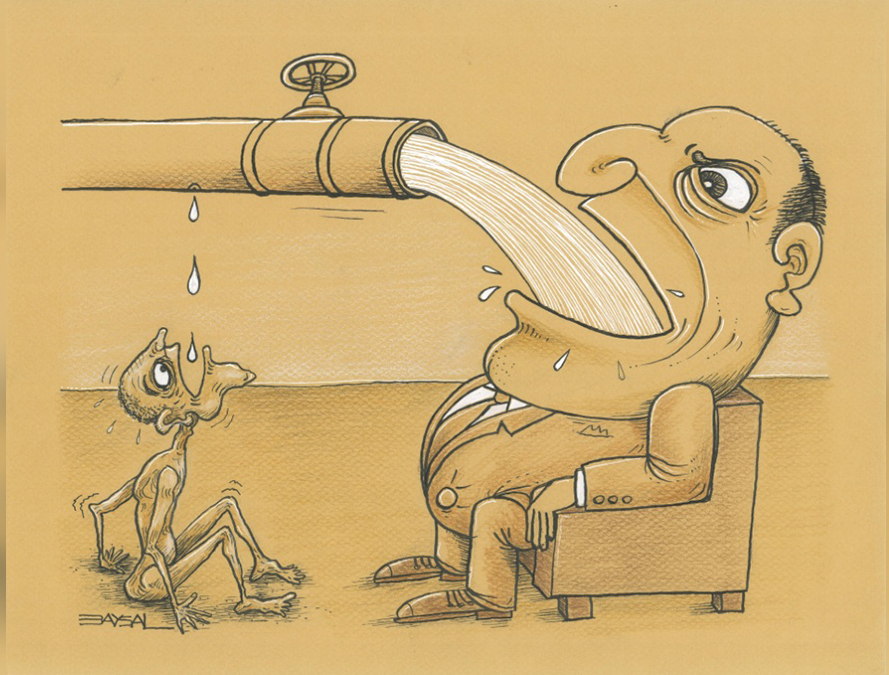

Cruel

Click to see definition

Causing pain or suffering to others

Behave

Click to see definition

To act in a particular way

Shame

Click to see definition

A bad feeling when others think you did something wrong

Guilt

Click to see definition

A feeling that you have done something wrong

Stability

Click to see definition

A situation where things stay the same and do not change suddenly

Terror

Click to see definition

Extreme fear caused by violence or threats

Dignity

Click to see definition

The quality of being worthy of respect

Chaotic

Click to see definition

Completely disordered and confused

Harsh

Click to see definition

Severe, cruel, or strict

Centralize

Click to see definition

To bring under the control of one central authority

Pax Mongolica

Click to see definition

A period of peace and stability across the Mongol Empire (Latin for "Mongol Peace")

Excluded

Click to see definition

Kept out or prevented from joining a group

Conscience

Click to see definition

An inner sense of what is right or wrong

Compass

Click to see definition

Something that helps you know what is right and what is wrong

Internalize

Click to see definition

To make attitudes or behavior part of your nature

Surveillance

Click to see definition

Close observation, especially of a suspected person

Primordial

Click to see definition

Existing from the beginning of time; ancient and fundamental

Neurobiology

Click to see definition

The biology of the nervous system and brain

Transcending

Click to see definition

Going beyond the limits of something

Codification

Click to see definition

The process of organizing laws into a systematic written code

Jurisprudence

Click to see definition

The theory and philosophy of law

Draconian

Click to see definition

Extremely harsh and severe (from Draco, the Athenian lawmaker)

Vendetta

Click to see definition

A prolonged bitter quarrel with violent revenge

Annihilation

Click to see definition

Complete destruction

Impunity

Click to see definition

Freedom from punishment or negative consequences

Anthropological

Click to see definition

Relating to the study of human societies and cultures

Ostracism

Click to see definition

Exclusion from a society or group

Autonomy

Click to see definition

The right or condition of self-government; independence

Circumscribed

Click to see definition

Restricted or limited

Transgression

Click to see definition

An act that goes against a law, rule, or code of conduct

Indoctrination

Click to see definition

The process of teaching a person or group to accept a set of beliefs uncritically

Visceral

Click to see definition

Relating to deep feelings rather than to careful thought

Vocabulary Quiz

Question 1 of 10

Writing Practice

What Drives Civilization?

In your opinion, which force is the most effective at maintaining order in society: Fear, Shame, Pride, Guilt, or Envy?

Write 150-250 words explaining your choice. Use examples from the lesson (Draco's laws, Genghis Khan, shame cultures, Viking pride, or guilt-based societies) to support your argument.

Consider: What are the advantages of your chosen force? What are the potential problems? Can you think of a real-world example from your own culture or experience?